In Casey McQuiston's Red, White & Royal Blue, Alex Claremont-Diaz (First Son of the United States) doesn’t exactly get along with Prince Henry of England. At first, he can't stand him. Henry is cold, reserved, and just a little too perfect. But after an international incident involving a royal wedding cake and an unfortunate photo, they’re forced to fake a friendship for the sake of diplomatic relations.

Cue forced proximity, enemies to lovers, and a hefty dose of grumpy/sunshine dynamics. It’s a romance that hits all the right beats. Tension turns to attraction. Banter turns to longing. And by the end, Alex and Henry have crossed oceans—literally and emotionally—to find their happily ever after.

But Red, White & Royal Blue isn’t just a love story, it may be a signal of something bigger happening in romance fiction.

It seems that romance novels are becoming more tropey—or perhaps readers are simply becoming more fluent in the language of tropes, increasingly labeling books with familiar patterns. Romance heroes seem to be getting softer, and heroines sharper. Content warnings like death, grief, and mental health have surged, suggesting that authors are tackling these themes more frequently, or at the very least, that readers are becoming more attuned to them.

To better understand how the genre is evolving, I scraped data from the top 250 romance novels each year, between 2009 and 2024, including tags and reader reviews to tracking which tropes are trending, the kinds of heroes readers love, and how the genre and readers alike are adapting to a new generation of romance.

Because while happily ever after might be guaranteed, how we get there has never looked more different.

Romance, Rewritten

What Today's Romances Say About Us

Kaitlyn Barbour

MICA DAV Spring 2025

"That was love stories 101. Happy endings had to be earned."

― Jodi McAlister, Not Here to Make Friends

Chapter 1

Tropes & The Stories We Tell

In romance, the ending is never a mystery. Readers expect a happily ever after (or at least a happy for now). What keeps us turning the pages is the journey: the tension, the banter, the misunderstandings, the longing glances across a crowded room, the occasional ‘there’s only one bed’ moments. And central to that journey is the trope.

A trope is a recognizable storytelling device—a shortcut that sets expectations. Think friends to lovers, fake dating, fated mates. Readers know the beats, but the excitement comes from seeing how they each get played out in a new way.

“The romance genre has been described as providing “surprise in comfort” because romance novels contain interesting twists on a familiar and satisfying narrative formula”

― Kolmes & Hoffman, "Harlequin Resistance? Romance Novels as a Model for Resisting Objectification"

It’s easy to dismiss tropes as a shortcut or an excuse to avoid creating original plots or characters. Books that lean heavily on familiar tropes often get criticized for being too cliché or for recycling the same ideas we've seen before. But there’s something beautiful about taking the familiar and breathing new life into it, or finding a fresh way to tell an old story.

TikToker Sanjana @baskinsuns likens romance in particular to mathematical proofs: “Why do we reprove things that have already been proven? … What does it mean for every romance novel to be an attempt at a more elegant, more amusing, more creative, more unique, more thoughtful way of arriving at this familiar destination?... In what ways can the romance novel be thought of as new proofs for problems that have been solved?”

Tropes can serve as effective marketing tools, especially in a saturated market. They offer a convenient way to position a book within the broader landscape of similar titles, helping readers quickly understand what to expect and how the book aligns with others they may enjoy.

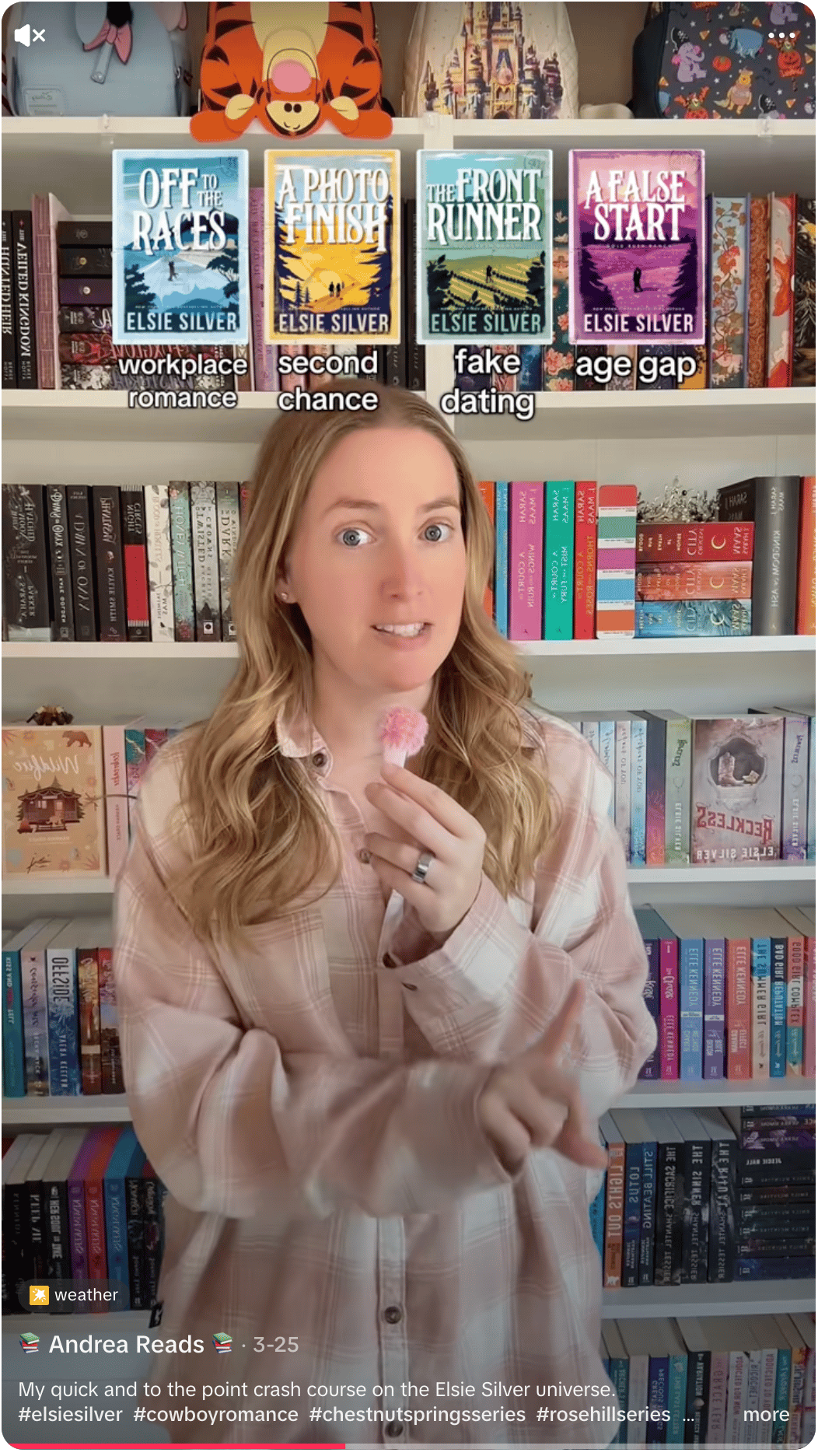

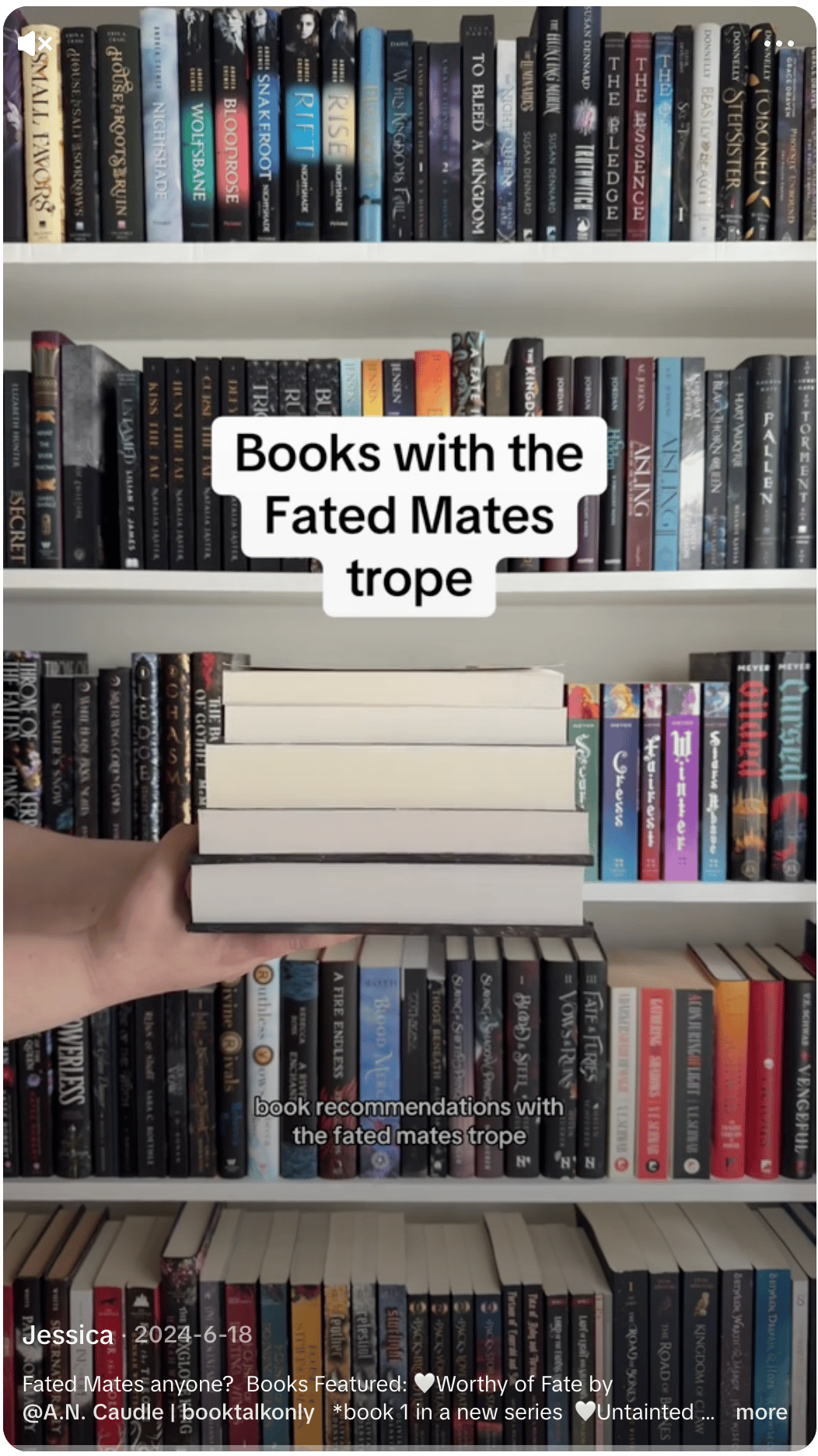

On platforms like TikTok and Instagram, tropes have become a kind of marketing shorthand and one of the main ways readers pitch books to each other. Instead of long summaries, people say things like childhood-best-friends-turned-academic-rivals-to-lovers, accidental-pregnancy-cowboy-romance, or second-chance-workplace-romance and instantly set the tone. Even microtropes like only one bed or who did this to you have taken on a life of their own, becoming a fast, fun way to get people excited about a story.

If you’re only looking at BookTok, it might seem like tropes are everywhere. But is that actually reflected in the books readers are picking up? Are these tropes truly more common, or are readers and content creators simply rallying around a shared language to boost visibility and engagement? It raises the question of whether we’re seeing a rise in trope-heavy storytelling, or just a rise in how we talk about and label it.

To explore this question, I collected data from Romance.io and Goodreads for the top 250 romance books checked out each year from the Seattle Public Library. Romance.io is a user-driven site where readers tag romance novels with a wide range of descriptors covering genre, setting, character traits, content warnings, and plot elements, including tropes.

For this project, I focused on the years 2009 to 2024. While the Seattle Public Library checkout data does date back to 2006, the books from earlier years lacked enough consistent tagging information to be useful for this analysis. For more details about how the data was gathered and processed, see the Data & Methods section.

the LANGUAGE OF LOVE

TRACKING THE RISE OF TROPE TAGGING from 2009 to 2024

As you can see, the data suggests that most tropes are on the rise, especially the top row, which takes off around 2019–2020.

The books are sorted by their 2024 rank, and the chart shows how often each trope appeared in the top 250 most-checked-out romance books from 2009 to 2024. Counts range from 0 to 140 books with each trope per year.

Big jumps across the board mean familiar plot elements are showing up in more and more books, or are at least being tagged with them.

The biggest overall winner is forced proximity, which showed up in 136 of the top 250 romances in 2024.

That means that more than half the list features characters being stuck together that eventually falling in love.

If we narrow in on growth, which tropes have changed the most in recent years?

All of these tropes have at least doubled since 2019.

The trope with the highest rate of increase is fated mates—up from just 6 books in 2019 to 37 in 2024.

That’s a 500%+ jump for soul-bonded lovers.

Some of the most popular trope tags in this dataset—like hurt/comfort, good grovel, and caretaking—have deep roots in fanfiction spaces, especially Archive of Our Own (AO3).

On AO3, tags aren’t just decoration, they’re a system. Fandom communities have built a shared language to flag everything from tropes and pairings to content warnings. This tagging culture acts like a reader–writer contract: readers get to make informed choices, and writers are expected to be upfront about what’s in their story.

Now, we’re seeing that same vocabulary cross into traditionally published romance. Tags that started as informal fan lingo are showing up on sites like Romance.io or in TikTok recommendations and shaping how books are described, marketed, and discovered.

I think it’s important to highlight the role of fanfiction here. Fanfiction isn’t just a niche corner of the internet anymore. As more readers engage with it, and as it becomes more visible, it’s started to shape the way we talk about romance. Tagging behavior, AO3-style vocabulary, and fandom-specific tropes are leaking into the language of traditionally published books.

In fanfic, tropes aren’t just plot devices, they’re cultural shorthand. Enemies to lovers, hurt/comfort, found family—each one comes with a set of expectations fan communities have fine-tuned over years of reading and writing. They’re more than labels; they’re part of a shared storytelling system. This tagging system isn’t just staying in fandom spaces. As fanfic readers move into the romance sphere, they’re bringing that language with them. Tropes have become a way to signal emotional tone, narrative style, and content at a glance.

Fanfiction isn’t just influencing romance: in certain cases, it is becoming romance. Over the past decade, several fanfics have made the leap from fandom favorite to published hit.

- Fifty Shades of Grey started as a Twilight fanfic (Masters of the Universe) and launched a full-on erotica boom.

- After, a One Direction AU with Harry Styles reimagined as a brooding bad boy, turned into a multi-movie franchise.

- The Love Hypothesis began as a Reylo fanfic and brought grumpy/sunshine, fake dating, and STEM girl romance into the spotlight, becoming a BookTok favorite at the same time.

The fanfic-to-trad-pub pipeline is still running strong. This year alone, three Dramione fanfics (stories pairing Draco Malfoy and Hermione Granger from Harry Potter) are getting traditional releases: Rose in Chains by Julie Soto, Alchemised by SenLinYu, and The Irresistible Urge to Fall for Your Enemy by Brigitte Knightley are all slated for release in Summer or Fall of 2025.

Even when these stories get repackaged for the bookstore, they keep their fanfic heart. Long slow burns, emotionally intense arcs, and deep character focus are all still there, and they’re resonating with a wider audience than ever before.

“I have a theory. Hating someone feels

disturbingly similar to being in love with them.”

― Sally Thorne, The Hating Game

Tropes don’t operate on their own, and most are deeply interconnected with each others. You expect enemies to lovers to come with forced proximity (why else would they be together!), and friends to lovers to stretch out into a slow burn. These combinations show up again and again because they work, and because readers expect them to.

Take Bride by Ali Hazelwood, a paranormal romance between a Vampyre and a Werewolf Alpha. Even without saying the words, the synopsis signals a stack of familiar—and currently very popular—tropes: marriage of convenience, enemies to lovers, forced proximity. It’s a great example of how tropes layer together to build stakes, tension, and emotional payoff.

Click below to explore how these tropes overlap. This chart shows which tropes most often appear together. The thicker the line, the more books share both tropes.

These connections show how tropes don’t just coexist—they work together to shape the emotional core of a story. The more we understand how they overlap, the more we can see how romance novels build familiarity, tension, and satisfaction with every pairing.

A big part of studying romance novels and fanfiction is understanding how our language around them has evolved. One key question is whether we’re seeing real changes in the stories themselves, or just changes in how readers are tagging and talking about them.

Take grumpy/sunshine, for example. It’s often cited as one of the fastest-growing tropes in recent years, but before 2020, it only showed up in around 20 books a year (out of 250). Still, the dynamic itself isn’t new. The classic “grumpy man and sunshine woman” pairing has been a staple of romance long before this trope had a name or a tag.

The timing isn’t random. Google Trends shows that searches for “grumpy sunshine” started to spike right around the same time that the number of books tagged with Grumpy & Sunshine began rising in my dataset. This suggests that the trope wasn’t necessarily becoming more common, it was just becoming more recognizable and talked about as we developed language for how to discuss this character dynamic.

You can explore the overlap for yourself below: the pink line represents the number of books tagged with the trope each year, while the blue lines reflect how often people were searching for it on Google over time.

Grumpy/Sunshine Glow-Up

As more readers searched for "Grumpy/Sunshine,"

more books started getting tagged with it

Grumpy/sunshine is a perfect example of how reader vocabulary and growing awareness can shape what we think we’re seeing in the data. The same could likely be said for other tropes, but this one stood out as the most dramatic case.

Still, even with shifting language, I’m inclined to believe that some tropes really are becoming more popular and genuinely show up more often in modern romance. But since this dataset relies on user-generated tags, there’s no definitive way to separate actual content trends from changing reader behavior.

"Apparently, there's someone for everyone”

― Emily Henry, People We Meet on Vacation

Chapter 2

Heroes, Heroines, & Who Gets a Love Story

There’s a lot of scholarship out there about romance novel characters, especially the men. People have been analyzing hero archetypes for decades, picking apart how these rugged, emotionally unavailable guys fit into or conflict with feminist ideals and gender expectations.

“Popular romance novels are often interpreted as providing insight into the way that women negotiate fantasy lives within patriarchal culture”

― Lee, “Guilty Pleasures: Reading Romance Novels as Reworked Fairy Tales”

But lately, something’s shifted. Maybe.

The old formula—she tames the brooding man and finds his soft side—is being replaced with something that feels... different. These days, the guy is often already soft. He’s perfect. He’s emotionally available. He’s obsessed with her from chapter one. And the heroine? She’s the one with baggage. Closed off. Prickly. Maybe even borderline unlikeable.

Take Book Lovers by Emily Henry. Nora Stephens is the classic "ice queen" (sharp, ambitious, emotionally guarded), while Charlie, her love interest, is broody but emotionally available and fully supportive. He doesn’t try to change her, he just gets her.

It’s less about winning over a tough guy and more about being loved without having to change who you are. Which honestly sounds great—but is it really new?

A Quick Note: While queer romances have increased over the years, there isn’t enough consistent tagging to break down how queer heroes might differ from straight ones, nor are there enough examples in my limited dataset. In this dataset, “hero” refers to the (typically more masculine) love interest in a romance—regardless of gender or orientation, as tagged by readers on RomanceIO. For now, all love interests are grouped under “hero” and “heroine” based on traditional role dynamics, not identity.

Heroes

The hero is central to the romance novel. There has to be enough tension between the characters (whether from clashing personalities or external plot drama) to sustain 80–110K words of slow build and emotional push-and-pull. But it can’t go too far—readers still have to believe these two will end up together in the end.

As one half of the central pairing, the hero has a lot to carry, and his masculinity is a big part of that. It shapes the tension, the attraction, and the emotional arc. However it’s portrayed, masculinity is key to how the hero functions in the story.

"The romance hero has to not only exhibit traits that are positively associated with masculinity but do so on an extraordinary level. His masculinity is essential to his ability to fulfil the romantic fantasy; he is the perfect life partner because of it”

― Kluger, "Post-Trump masculinity in popular romance novels"

On Romance.io, male love interests are tagged with all kinds of personality traits—from bad boys to himbos to grumpy/cold hero. To make sense of it all and analyze similar ideas together, I grouped the most common tags into five broad archetypes:

- Dominant & Possessive (alpha male, possessive hero)

- Dangerous & Edgy (bad boy, cruel hero/bully)

- Emotionally Guarded (grumpy, shy)

- Unassuming (himbo, nerdy)

- Warm & Gentle (sweet, sunny)

Each of these categories reflects a different kind of fantasy and a different idea of what makes a hero swoon-worthy.

So how have these hero types changed over time? The chart below tracks the rise and fall of each category, showing which kinds of male characters are showing up more often and which ones might be fading out of the spotlight.

From Brooding to Boyfriend Material

The rise of the warm, gentle romance hero

What we’re seeing here is a clear gentling of the male lead. Between 2016 and 2020, Dominant & Possessive heroes dropped off noticeably, while Warm & Gentle heroes rose to take first place. Since 2019, dominant heroes have made a bit of a comeback, but not to their former levels, and by 2024, they’re still outpaced by their softer counterparts. Also worth noting: Unassuming heroes—like nerds and himbos—have been steadily climbing, reinforcing this shift toward more emotionally available, low-drama love interests.

And unlike tagging shifts, this feels like a real change in content. More books are actually featuring these softer, more emotionally available men at the center of the story.

So what’s behind this shift toward warmer, gentler male leads? It’s likely not just a trend within publishing, it reflects broader cultural and political changes.

In recent years, conversations around masculinity, consent, and emotional accountability have become far more mainstream. Movements like #MeToo challenged the normalization of coercive or predatory male behavior, bringing issues of power, gender dynamics, and bodily autonomy into the public eye. At the same time, political events—like the election of Donald Trump in 2016, his reelection in 2024, and the public allegations about his conduct toward women—sparked widespread backlash and increased scrutiny of how masculinity is portrayed in media.

Romance, as a genre that centers emotional intimacy and desire, doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Authors, readers, and publishers are all responding to these conversations, sometimes consciously, sometimes not. The fantasy is shifting: instead of taming an emotionally unavailable alpha, many readers are craving love interests who are safe, supportive, and emotionally fluent from the start.

This doesn’t mean dominant or edgy heroes have disappeared altogether, but their appeal may now sit alongside a stronger cultural desire for softness, sincerity, and equality in romantic dynamics.

“The new romance hero’s characteristics reflect an attempt to differentiate this figure... from the kind of man that exploits positions of power and authority in order to undermine women’s rights of self-determination, presenting instead a character who uses his power to uplift and support the women in his life.

This change should be read as a continuation of a development that precedes the Trump era but that was exacerbated and made more explicit in its wake.”

― Kluger, "Post-Trump masculinity in popular romance novels"

Ultimately, the romance hero isn’t just a character—he’s a reflection of what readers want, fear, and long for in a partner. His role has always been shaped by cultural values, and right now, that means moving toward emotional availability, gentleness, and mutual respect. As Johanna Kluger put it, “The romance hero has always been a vessel for women to project their needs and desires onto, and thus, must evolve with the times.” And it appears he has evolved: from untouchable alpha to golden retriever boyfriend, the hero continues to shift in response to the world around him.

“I love you,’ he whispered, and kissed my brow. ‘Thorns and all.”

― Sarah J. Maas, A Court of Thorns and Roses

Heroines

If male characters are evolving, what about the heroines? Using Romance.io tags, I grouped common personality traits into three broad archetypes:

- Warm & Sweet (cheerful, gentle)

- Bold & Rebellious (sassy, female rake)

- Strong & Independent (competent, take-charge, independent)

- Reserved & Guarded (ice queen, shy)

While most categories have stayed relatively stable over time, one stands out: Strong & Independent heroines have seen a major rise—suggesting a shift toward female leads who are capable, self-reliant, and often emotionally walled-off in ways that used to define the male hero.

In 2009, only 86 of the top 250 books are tagged with Strong & Independent heroines

By 2019, Strong & Independent began to grow - 108 of top 250 book heroines listed included this tag

By 2024, a whopping 175 books listed Strong & Independent heroines.

That’s nearly double the amount from 2009!

How has the rise of romantasy/fantasy romances shaped this rise?

When we break down the books tagged with Strong & Independent heroines in 2024 by genre, most are categorized as either Romance or Fantasy.

While male leads in romance are softening, heroines are holding steady, or even growing stronger. In my dataset, the Strong & Independent heroine category has seen a significant rise. In 2024 alone, 175 books were tagged this way, with 69 of them falling into the fantasy genre. That isn't surprising, since fantasy settings often demand heroines who can wield swords, command armies, or outwit magical foes.

But this increase is seen in contemporary romances too. In Yours Truly by Abby Jimenez, Dr. Briana Ortiz is tagged as an independent, competent, and take-charge heroine. She’s a career-driven ER doctor juggling a demanding job, family responsibilities, and her own emotional recovery. But would we have called her “strong and independent” 10 years ago? There's a chance, but maybe she would have just been seen as a typical romance heroine. These traits have always existed, but they maybe weren’t always labeled so directly.

So why the uptick in "Strong Heroines" now? It could be that readers and reviewers are more tuned in to these qualities, more eager to name and celebrate them. The rise of platforms like Romance.io and Goodreads has made it easier for readers to share their interpretations, leading to more detailed, varied, and values-driven tagging than we might’ve seen in earlier years.

This is one of the trickier questions to untangle when analyzing shifts in romance. Is the rise in Strong & Independent heroines a real change in content—or just a change in language? It’s hard to say. Maybe it’s like the grumpy/sunshine example I gave above, where the dynamic existed long before we had a name for it. Maybe it’s because we simply have more robust tagging data for recent releases. Everyone has their own way of deciding what “strong” or “take-charge” looks like in a character, and there’s no data on when or why someone decides to tag them that way.

There could be plenty of older books with heroines just as bold, competent, or guarded as today’s, but they’re not tagged that way, either because fewer readers are engaging with them or because the vocabulary wasn’t there yet. Or maybe the tagging is accurate, and there really has been a shift in how heroines are written. I can’t say for sure unless I read every book in the dataset (and while I think I'm a fast reader, I normally only finish around 100 books a year).

Still, it’s an important question. Whether it’s a shift in storytelling or a shift in language, it reflects broader cultural conversations about gender, identity, and how we choose to frame strength in romance fiction. I’m inclined to believe it’s a bit of both—especially with the rise of romantasy, where high-stakes settings demand characters who know how to take control.

“I’m not going to die today.”

― Rebecca Yarros, Fourth Wing

Chapter 3

Content Warnings & Reader Sensitivities

One of the most fascinating parts of this dataset is looking at how readers tag content warnings. It’s a useful way to see not just what’s in the books, but what potential triggers people are paying attention to. Most content warnings have stayed pretty stable over time, but a few have spiked dramatically: death & grief, abuse, and mental health. These three warnings have seen consistent, noticeable growth since 2019/2020.

Tracking Content Warnings Over Time

The growing presence of grief, abuse, and mental health themes since 2020

What's behind this jump in content warning tags? Are death, mental health, and abuse actually appearing more often in our books, or are people just tagging them more?

They may or may not actually be more frequent (and from the data I have I cannot argue a definitive increase for sure), but it appears to me that the rise is from audiences being more aware and more invested in making sure fellow readers are appropriately warned.

Death & Grief

First, let’s look at the sharp increase in death tags—one of the most dramatic jumps in the dataset. This includes subtags like death/grief, miscarriage/infertility and terminal illness, grouped under the broader Death & Grief category.

Where are we seeing these increases? Is it all romance subgenres across the board?

Tracking Death & Grief Tags Across Genres

Fantasy and historical Show the Largest Growth in the Percent of Books Tagged

So what does this tell us? In fantasy, death is expected—it’s baked into the worldbuilding, the conflict, the stakes. Think of a book like Fourth Wing, which opens with characters falling to their deaths, or A Court of Thorns and Roses, where war between fae factions is central to the plot. Loss, violence, and grief are part of the genre’s DNA. So it’s not surprising to see a rise in Death & Grief tags within fantasy romance.

In historical romance, the rise might be tied to realism and context—these stories are often set during wars, pandemics, or eras with high mortality and strict social expectations. Grief, especially tied to lost love or duty, is often used to heighten emotional stakes or create second-chance arcs.

But the rise in contemporary romance specifically is a little different. This rise could mean that more romance books are engaging directly with themes of loss and emotional trauma. Or, it might reflect growing reader sensitivity: people want to be prepared for heavier content, even in genres known for their happily ever afters.

Take Beach Read by Emily Henry. On the surface, it’s a classic opposites-attract rom-com. But underneath, it’s a quiet, poignant exploration of loss. January is reeling from the sudden death of her father and the unraveling of everything she thought she knew about him. Her grief and identity crisis run parallel to a slow-burning romance that unfolds with tenderness and emotional honesty. It’s a perfect example of how modern romance is making more space for emotional complexity, where the happy ending doesn’t erase the heaviness, but exists alongside it.

Abuse

Unlike Death/Grief in fantasy books, the rise in Abuse tags doesn’t necessarily mean there’s been an increase in abuse-centered romance stories. Instead, it looks more like a shift toward more thorough and intentional tagging.

If we break down the subtags, most of the growth comes from past abuse—including past child neglect, past child abuse, and other trauma in a character’s backstory. Third-party abuse has also gone up slightly, but still makes up just about 1% of the dataset. Abuse between main characters has stayed consistently low.

All of this suggests that readers aren’t asking for more stories about abuse, they just want to know when it’s there. Tagging helps readers make informed choices and avoid content that could be distressing, especially in a genre where emotional safety is often part of the promise and appeal.

Tracking Abuse Tags Across Genres

Increases are mostly from past abuse, not between main characters

It’s reassuring to see that abuse between main characters has remained low in the dataset—most readers just don’t want to see that dynamic romanticized. One of the most mainstream exceptions is Colleen Hoover’s It Ends With Us, which follows Lily Bloom as she falls for the charming Ryle Kincaid—only to find herself in a relationship marked by abuse that mirrors her childhood trauma. As she tries to break the cycle, she reconnects with a past love who offers a safer alternative.

The book has sparked debate: some readers appreciate its emotional complexity, while others argue it romanticizes harm. The controversy grew louder with the upcoming film adaptation, especially after promo materials were criticized for glamorizing domestic violence.

Abuse-focused stories don’t sit easily within a genre where a happily ever after is usually expected. The tension between emotional realism and romantic fantasy is exactly why content warnings matter, and why tagging is more important than ever.

Mental Health

Just like Death/Grief and Abuse, there’s been a noticeable rise in Mental Health content warnings across recent romance novels. The underlying tags that were grouped into this include mental illness, mental trauma, self-harm, and suicidal ideation.

Anecdotally, there also seems to be a shift toward more explicitly named mental health conditions. Characters are no longer vaguely “troubled” or “closed off”—they’re described as having PTSD, OCD, ADHD, anxiety, autism, and more.

Where do we see these changes?

Rise of Mental Health Themes

Percent of Books Tagged seems to be increasing in top genres

The rise in Mental Health tags shows up across basically all major romance subgenres, very notably so in Romance, Historical and Fantasy—but what’s driving it? It’s hard to say for sure. Part of it is likely increased sensitivity; readers are more aware and more likely to tag mental health themes when they see them. But it also feels like an actual shift in the content itself. More books are acknowledging anxiety, trauma, and neurodivergence directly, rather than dancing around it.

It points to a broader change in the emotional core of romance: moving away from the old “you have to love yourself first” narrative, and toward something more accepting. Something more like “come as you are.” With more books embracing neurodivergence, mental health challenges, and emotional messiness, the HEA feels less like a finish line and more like a supportive starting point. This “come as you are” mindset reshapes what happily ever after means. It’s no longer about being perfect, but about being understood. It's about finding someone who sees the flaws, the baggage, the panic attacks or self-doubt, and says “yeah, I still want all of that.”

While this dataset focuses on user-generated tags, future studies could dig deeper—looking at the actual text of reviews or even the books themselves. Are terms like anxiety, ADHD, depression, and PTSD showing up more often in the narrative? Are authors naming these conditions more explicitly? That kind of analysis could help confirm whether we’re seeing a real shift in content—or just a shift in how readers are talking about it.

Content Warnings from Authors

While this dataset focuses on reader tagging, it’s also worth asking: are authors themselves offering more content warnings? Anecdotally, the answer seems to be yes.

More books are including trigger warnings at the start, ranging from emotional to darkly humorous. Brynne Weaver's Butcher & Blackbird famously includes “Accidental cannibalism” and “Not-so-accidental cannibalism.” Kate Stayman-London's Fang Fiction warns readers that the story follows a sexual assault survivor’s healing journey, supported by community... and sexy vampires. Even in more traditional contemporary romance, like Say You’ll Remember Me by Abby Jimenez, readers are informed about “detailed descriptions of someone with advanced dementia” and “a scene where a dog is in peril.” These author-added notes point to a growing awareness around emotional safety and reader consent.

But that transparency doesn’t always show up on the outside of the book.

Everyone has heard "don't judge a book by its cover," but the changes to modern romance cover aesthetics over the past 5+ years have made that more difficult. The Pudding has a wonderful piece called "What Does A Happily Ever After Look Like?" that visually explores the changes of romance covers, showing how raunchiness has been basically removed, while illustrated covers are up. This change is incredibly important.

Romance now looks much more appealing and sanitized, it's cuter, brighter, and looks very PG on the outside, even when the content is absolutely not.

Take Hannah Grace’s Icebreaker series. At a glance, the illustrated covers suggest a light, possibly young adult sports romance. But the content is definitely not appropriate for a young adult audience. TikTok is full of stories about middle schoolers picking up these books, only for parents or teachers to discover that they’re packed with explicit scenes. It’s not hard to see why this happens; most parents don’t have time to pre-read everything their kid brings home, and nothing about the cover screams “steamy college romance.” It’s a perfect example of how this new visual style can be misleading.

Take a second to flip through the carousel below. Check out the covers, read the tags, and compare the cover images to the actual “steam level” readers are associating with these books.

While “discreet” covers are meant to reduce stigma and boost appeal, they’ve also removed one of the genre’s key signals about what kind of emotional and physical intensity readers should expect inside. All of this raises an important question for future investigation: how are visual cues, content warnings, and tagging systems working together (or not) to help readers find the stories they’re looking for?

"People think romances are just about sex—and some are, which is fine—but they’re also about social change and challenging the status quo, such as who the world thinks deserves a happily ever after.”

― Christina Lauren, The True Love Experiment

Epilogue

Whether or not you think it's silly, romance has become one of the fastest-growing and best-selling genres in publishing. In 2023 alone, romance novels sold 39 million copies in the U.S.. By some accounts, it's a "billion dollar industry." Others refute this claim and say there's just not enough data to support that figure, but that it ultimately doesn't need to be a billion dollar industry for us to think it's worthy of consideration.

More importantly, beyond just the numbers, there’s been a real cultural shift around romance. If everything above doesn’t convince you that the genre and how we talk about it is changing, I’m not sure what will.

People aren’t hiding their love of romance anymore. Readers are proudly sharing their favorite books, authors, and tropes online. Series like A Court of Thorns and Roses and Fourth Wing have taken over the New York Times bestseller lists—despite the fact that there's no dedicated romance category. And that visibility matters.

The rise of romance-specific bookstores shows just how much the genre’s cultural status has changed. The Ripped Bodice, which opened in California in 2016 as the first dedicated romance bookstore in the U.S., was such a success it expanded to Brooklyn, and helped pave the way for more. Today, there are over 30 romance-focused bookstores across the country, from A Novel Romance in Louisville to Blush Bookstore in Wichita.

Where previous generations might have hidden their Harlequins, today’s readers are proudly posting, reviewing, and recommending romance. Some are even reclaiming terms like smut as a form of empowerment because these books center women’s desires, sexuality, and interior lives. As bookstore co-founder Leah Koch Kanter put it, “Romance is a powerful way for women to reclaim something that belongs to them.”

“The novel may not be a barometer of social history, and is never a simple reflection of its times, but what it can do is to chart the limits and shifts in social discourse”

― Arvanitaki, “Postmillennial femininities in the popular romance novel”

Let's go back to the idea of tropes or trope language increasing. As romance becomes more popular—and more commercialized—we need better, sharper language to market books. Since the Happily Ever After ending is guaranteed in romance, it's all about how we get there. Marketing by trope lets readers know where the plot fits in comparison to other books they may already know.

But the more we name tropes, the more people learn the language—and start applying it to everything. That creates a feedback loop: more tags, more niche terms, more ways to describe the same beats in new ways. Platforms like TikTok and the rise of romance bookstores are working in tandem here. They're not just selling books, they're creating a shared language that’s helping the genre grow in every direction. Just like the case of grumpy/sunshine, it's likely that we will see an explosion of certain tropes as terms as time goes on, which may not be a fundamental change in the content of romance novels but more a reflection of our newly developed vocabulary

Romance has always been a space for fantasy and escape, but lately, it’s also become a place where readers can feel seen. Beyond the tropes and the happy endings, romance novels are telling stories that deal with real challenges: mental health, trauma, grief, and healing. And for many readers, that kind of representation can be powerful.

More and more romance books are featuring characters who live with anxiety, PTSD, chronic illness, and more. In Get a Life, Chloe Brown by Talia Hibbert, the heroine navigates love and life while dealing with chronic pain, a story that mirrors the author’s own experience with fibromyalgia. Books like The Love Act by Zara Bell include open discussions about panic attacks and therapy, showing that mental health struggles don’t disqualify someone from a love story.

Romance is also tackling difficult topics like past abuse and trauma. In Blue-Eyed Devil by Lisa Kleypas, the heroine’s journey includes surviving domestic violence and slowly rebuilding trust. These stories offer a path toward healing and show that love can be safe, supportive, and restorative.

Books like Before I Let Go by Kennedy Ryan and You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty by Akwaeke Emezi explore what it means to grieve and still move forward. These stories don’t shy away from pain—they show how love can exist alongside it, and how characters (and readers) can find light even in the darkest chapters.

These stories remind us that you don’t have to be perfect or healed or whole to be worthy of love, you just have to be human.

"There is no happy ending, there's just happily living. As best you can."

― Ashley Poston, The Dead Romantics

Data & Methods

Sources

To conduct this analysis, I drew from three primary data sources: RomanceIO, Goodreads, and the Seattle Public Library.

The Seattle Public Library data source was selected to provide a yearly view of what people are actually reading. Comprehensive sales data is difficult to obtain—Amazon’s weekly data only extends back to around 2011, the New York Times focuses solely on fiction, and neither source offers detailed information specific to the romance genre. In contrast, SPL’s publicly available checkout data extends back to 2005, is well-documented, consistent, and provides a clear record of readership trends over time. While it primarily reflects traditionally published authors and lacks representation from the self-publishing space (such as Kindle Unlimited), it is one of the most reliable datasets available for this purpose.

RomanceIO and Goodreads were used to capture user-generated data, including reviews, ratings, and tagging behavior. These platforms offer insight into how readers themselves describe and engage with romance novels, making them especially valuable for identifying trends in tropes, character archetypes, and thematic elements.

Collection Process

To identify the most-read romance novels over time, I used the Seattle Public Library’s publicly available checkout data. I filtered the dataset to include items where the subject was listed included “Romance,” (which included items like Historical Romance, Paranormal Romance, etc) and then performed additional cleaning in Tableau to refine the dataset. This included:

- Removing non-romance items misclassified under the subject (e.g., Arthurian romance).

- Filtering to include only books (excluding movies, CDs, and other media formats).

Standardizing author and title formats to ensure consistency. - Consolidating multiple formats (e.g., audiobook, large print, eBook) under a single title to avoid duplication and produce more accurate checkout counts.

From there, I exported the top 200 most-checked-out romance books per year, later expanding the list to the top 250 per year for consistency and broader coverage.

I then used Python to scrape both Goodreads and RomanceIO. This process involved querying each platform to find unique book ID before using those IDs to scrape relevant data from individual book pages, including tags, reviews, and ratings.

Cleaning & Structuring

In cases where a book could not be matched on Goodreads or RomanceIO via my scripts, I tried to manually search for those titles and find their IDs. If I couldn’t find an item, the title was excluded and replaced with the next book on the list. In a few cases, older books occasionally only appeared as part of anthologies, so I also excluded those items and replaced them with the next book on the list since they included combined tags for multiple books under the same ID.

To make the tag data more interpretable, I grouped individual user-generated tags into broader thematic categories. This was done for key areas of focus, including:

- Tropes (e.g., combining “cheating” and “other man/woman” into a broader category)

- Character archetypes (e.g., sweet, sunny, etc.)

- Subgenres

This categorization allowed for clearer trend analysis without losing meaningful nuance.

The scraping process began on February 4, 2025, and the last books were scraped on March 20, 2025. Since both Goodreads and RomanceIO rely on user-generated tags, the data is inherently dynamic, and tags may continue to be added over time. While tags rarely disappear, this time frame is worth noting for anyone attempting to replicate the results, as scraped data could differ slightly depending on when it is collected.

Challenges & Limitations

A central question throughout the project was whether the available data was sufficient, and whether it was overly skewed toward recent publications. The most challenging aspect was determining if the trends I observed, particularly the increase in tropes, reflected actual changes in publishing and reader preferences or were simply a result of recency bias in the data sources.

Striking the right balance between capturing real change and avoiding recency bias was a key challenge. To evaluate whether newer books were genuinely more “tropey” or just more heavily tagged, I looked at the average number of trope tags per book across the time period. As expected, there was a noticeable increase in trope tags after 2020. However, to check whether this reflected a broader tagging trend, I also looked at other categories such as genre and setting tags. These remained relatively stable over time, suggesting that the rise in trope tagging is more specific and not just a result of newer books being more tagged overall.

After reviewing the completeness and quality of the data, I chose to exclude the years 2005–2008. These years contained a lot of missing or sparse metadata, particularly in user-generated tag data, and didn’t offer enough consistency to support reliable conclusions. By focusing on the period from 2009 onward, the dataset remained rich enough to analyze while minimizing the risk of distortion from incomplete early records.

Sources & Acknowledgements

I want to extend a huge THANK YOU to my people for all your help!

- To Emma—for offering an author’s perspective and insights from inside the publishing world, and for helping me realize I was on the right track with romance bookstores, tropes, and beyond.

- To Sanjana—for your thoughtful takes on BookTok, tropes, and how readers think about tagging and reviewing. You helped me clarify my arguments and reminded me not to overstate how much is "changing."

- To my usability testers and fellow romance readers—Alli, Julia, and Emily—for being incredible sounding boards, pushing me to add what I missed, asking sharp questions, and giving feedback that made this project so much stronger.

- To Amy, Jes, Tracy, and my MICA cohort—your weekly feedback and support kept me moving forward and made this project possible.

- To my parents—thank you for instilling a love of reading in me, for my Kindle, my library card, and all the book recommendations. Also, thank you for not saying I was crazy to want to do a graduate program, and for supporting me and my projects every step of the way.